Happy Year of the Monkey! Decrypting Chinese New Year’s Symbolism in UI Design

新年快乐! The Chinese mainland is ringing in the Year of the Fire Monkey, and I, for one, welcome this opportunity to pay homage to the joys of opposable thumbs, prehensile tails and the singular excitement of flinging my own excrement.

Just as the Christmas season on the Western web gives rise to endless reindeer vectors and jQuery-powered snow, around the Lunar New Year, the Chinese internet likewise lights up with festive interfaces rich in holiday symbolism (and since China is mobile-centric, lots and lots of light apps). In celebration of the Spring Festival, we’re going to take a quick peek at the meaning and history of traditional Chinese New Year visuals, and we’ll look at some example interfaces which incorporate those seasonal themes.

Note: we’re busily translating Envato Tuts+ into Chinese (among other languages), check out these archives, and get involved!

- Web Design tutorials: Chinese (Simplified) and (Traditional)

- Design & Illustration tutorials: Chinese (Simplified) and (Traditional)

- Code tutorials: Chinese (Simplified) and (Traditional)

- Photography & Video tutorials: Chinese (Simplified) and (Traditional)

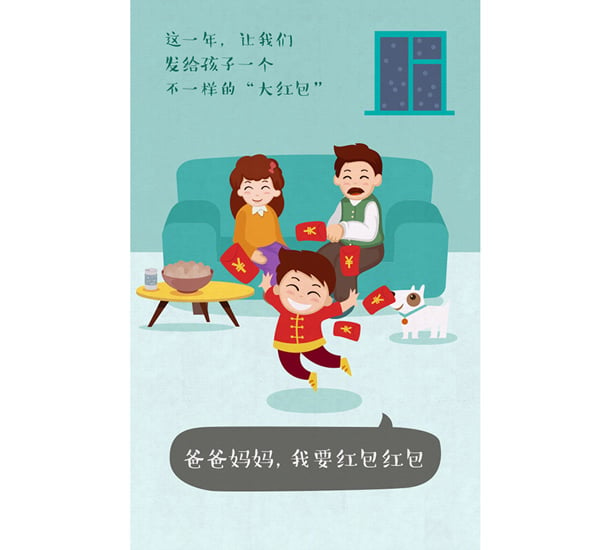

Red Envelopes (hongbao)

In one New Year’s custom (which basically boils down to trick-or-treating for money) children traditionally harangue parents and older siblings with cries of “hand over the red envelope!” and elders are expected to pony up some spending cash.

The practice of giving hongbaos to kiddos supposedly originated sometime during the last imperial dynasty. According to one of many legends, strings of coins tied with red ribbon were placed under the pillows of village children to ward off marauding demons (it’s a long story.) With the rise of the printing press, the ribbons became envelopes, and so the modern holiday tradition was born.

Heavy use is made of this visual imagery in digital marketing, particularly for ecommerce sites, with discounts and promotions “delivered” in red packets, called hongbao.

For example, this seasonal light app design for Pingan promoting children’s insurance, reads: “This year, let’s give the children a different kind of red envelope”. Child: “Dad, mom, I want a hongbao!”

Receiving a 100 renminbi promotional gift from Touzila.com, a financial management platform, by 蝴蝶结秀:

In this light app mini-game, the mischevious Monkey King has ten seconds to crack open a red envelope and win. “You succeeded in bursting the red envelope, quick, claim your prize!”:

Customers scramble to snatch red envelopes out of the air in Taobao’s Spring Festival deals page header:

Turn That Fu-wn Upside Down

Here’s a perfect example of a cross-culture conceptual mix-up waiting to happen: in the west, when we see something turned upside down, we often take this to mean that its original significance has been overturned, that it now has the opposite significance. When we say something was “turned upside down”, we mean that it was thrown into disarray.

Not so in China. Meet the Chinese character ‘fu’. It means “luck” or “prosperity”.

In Chinese language, the word for “arrive” sounds very similar to the word for “upside down”. So, turning the “fu” upside down creates a visual pun, which means “prosperity has arrived”. Eh? Eh? Get it?

An upside-down “fu” is one of the most common Chinese New Year’s symbols, and many families hang placards depicting the inverted “fu” on the front door, much like a Christmas wreath. “Fu” is typically displayed right-side up inside the home, and upside down on the door.

Below: “No matter where you are, Good Flavors will follow you.” In this case, “fu” is shown upside-down on the yellow globe.

Neon-style banner of well-wishing: “Auspicious Monkey Year”. See the upside-down fu in the diamond on the right?

And here we see fu right-side up (behind the performers on the left screen). Left screen text: “In the past, the only thing to do on New Years Eve was watch the annual Spring variety show.” Right screen text: “Today, everyone can celebrate New Years Eve the way they want.”:

Spring Couplets (Chunlian)

The Chinese couplet, or duilian, has been in use for about 1000 years. It’s a two-line poem typically displayed vertically on strips of paper which are pasted on either side of a doorway. Special couplets are written for display during the Spring Festival season–these are chunlian.

Couplets usually express feelings of renewal or pleasant sentiments for a budding year. But in interface design, they’re often used as a location for central messages, creative content or flavor text.

Here’s a screen from a mini-game light app–the couplet is around the door on the left screen. No marketing copy on this chunlian, just a classic poem of new beginnings: “The horse’s hoof breaks the snow of the old year, the magpie ascends the plum tree to announce the coming of spring.”

And here, a promotional intro screen for Miaoqian. The couplet to the left and right of the door reads: “For investment and financial services choose MiaoQian // Out with the old: welcome the Year of the Monkey”.

Below, the people on the right hold up a couplet reading, “It’s only Chinese New year if you eat and drink well // Buying New Years goodies solves all problems.”

Family Harassment

Let’s not get too sentimental here, shall we? Western

holidays aren’t all candy canes and chocolate baskets. Going home is always a

bit of a mixed bag. Yeah, you get to sleep in your old room and there’s a

fridge full of cookies, but you’re also probably going have to listen to at

least one uncle explain how the pine oil lobby is undermining the foundations

of democracy and somebody’s definitely going to make you eat a cheese ball when you’re way too full.

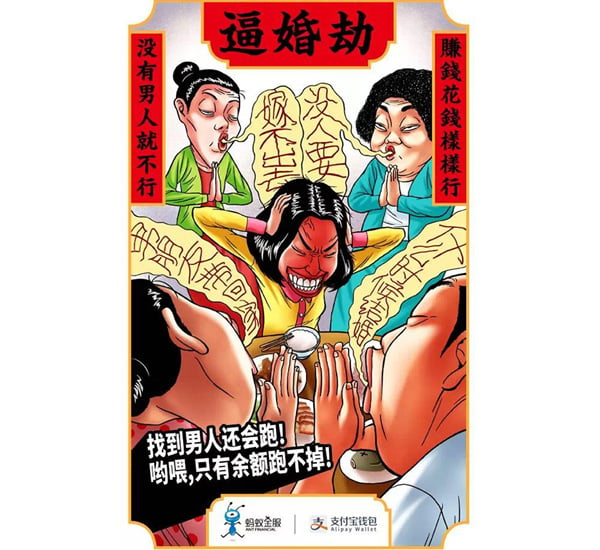

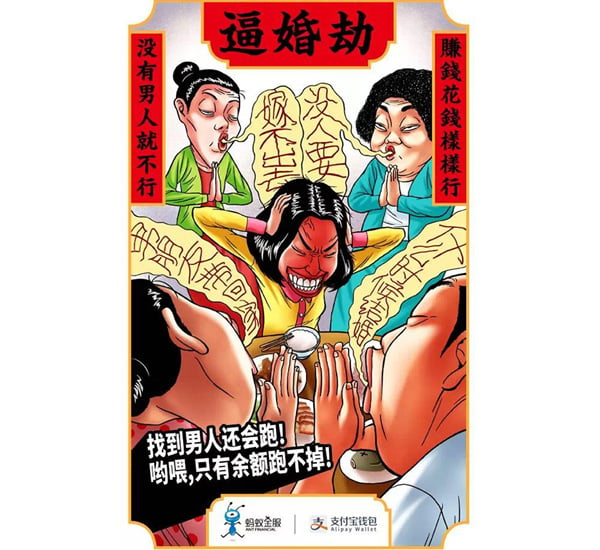

In this struggle, all nations are one. Chinese New Year comes with its own set of homecoming tropes that are heavily drawn upon by light app designers, one of the more persistent themes being family pressure.

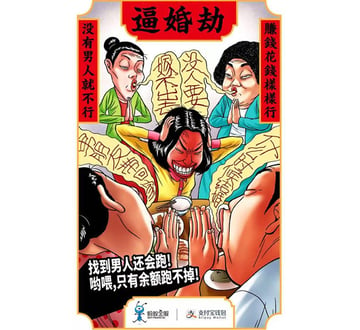

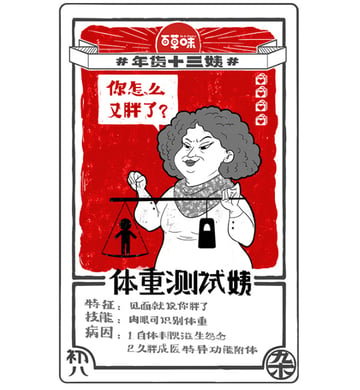

Unmarried? Every single one of your aunties will give you grief for being single after the age of 25. Married, no kids? Still no joy. Married, kids, house, car, no promotion? You bring shame upon this house, child.

Take Alipay Wallet’s promotional light app. “Why aren’t you married?“ ”No one wants a girl who...” “...bring your boyfriend home to meet us.” “When are you going to get married?” You’ll notice there’s also a couplet on the red strips on the top left and right, which reads “Make money, spend money, everything’s fine / it doesn't matter if you don't have a man.”

The thirteen Aunties of New Years: Auntie of the Scales says, “How did you get even fatter?”

Firecrackers

If you’ve never seen the business end of Chinese New Year’s Eve in Beijing, put it on your bucket list. A sea of fireworks like a coral reef in the sky, and they don’t stop for a week. But what’s up with the beautiful pyromania?

According to yet another hazy legend about yet another beastie in yet another village, once upon a time, the slavering fiend Nian came out of hiding each winter to devour unlucky townsfolk. One year, as Nian approached, he was startled by the sound of bamboo cracking on a bonfire, and off he ran. After that, explosions became a mandatory kickoff to a prosperous year–they scare off bad luck and get things underway with all appropriate pomp.

Yihaodian.com has a kid setting off fireworks near the logo:

Fire-happy monkey in the liveapp.cn header:

Use the firecrackers to blow red envelopes out of the dragon's mouth:

Caishen, God of Wealth

Play a mini-game to win prizes, delivered by the money man himself:

Everybody loves this guy. He has great taste in hats and he never lets anyone else pay for dinner. Like every story which goes back a few dozen generations, Caishen’s legend is conflicted and tangled. Suffice to say, whither goes Caishen, money goes also, and so his image is hung in the home to welcome financial prosperity in the new year.

A QVC-style sales page for a Caishen figurine:

Registration callout for online banking “Click to register and login / Start your smart prosperity plan!”:

Monkeys, Monkeys Everywhere

Last but not lagging, our seasonal mascot for 2016. The monkey, one of China’s most beloved zodiac animals, is considered the cleverest and most cunning of the celestial pantheon. In popular culture, the monkey is most frequently embodied in the trickster god Monkey King from the classic work of Buddhist fantasy literature, Journey to the West.

Chinese New Year visuals typically indicate the zodiac year, and websites often temporarily decorate by placing the current year’s animals in headers. In 2015, for example, we were bombarded with sheep-themed sites, and the year before that, horses.

The Monkey King on a page banner for Quwan.com:

Here’s a monkey-themed red envelope prize game:

And a concept mockup for a year-end corporate light-app:

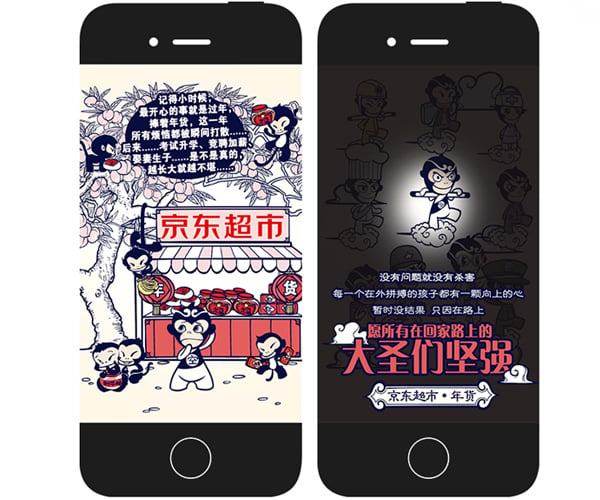

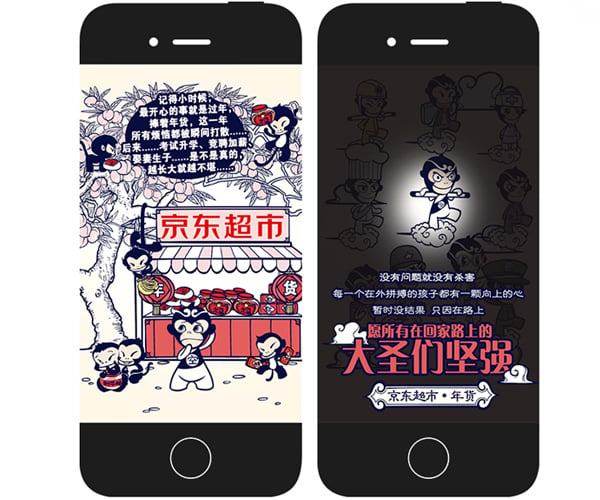

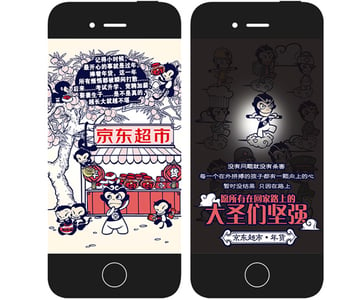

Jing Dong Supermarket promotes its New Year’s selection through a story about the Monkey King’s return home for the holidays.

This ecommerce banner brings it all together with couplets, monkeys, and inverted “fu” lanterns:

All Together Now:

“Happy New Year!”